By Linda Hosek

If you’re a photographer who wants to build a following for your photos, try posting a failure, such as a bad print, on social media. But don’t stop there. Share how you turned that rejected print into one you really like, one that represents your personal vision or “fingerprint.”

“It’s how to build long-term loyal collectors who stay with you,” says Michael Foley, a gallerist who owns Foley Gallery in New York City. “You have to allow yourself to be vulnerable, but wrap it into something helpful for others.”

Foley, also an educator who serves on the faculties at the International Center of Photography and School of Visual Arts, will teach a workshop on “Choosing Yourself as an Artist” via Zoom at the SE Center for Photography in Greenville, South Carolina. The event, May 11-12, is for photographers who want to move their career forward without gallery representation or exhibitions. The idea is to proceed with a self-endorsement or belief in your own images.

“I want an artist to feel empowered, to move their work forward at their own speed and not wait for someone to tell them the can come into the club,” he said.

Foley’s strategy is not about wishful thinking. It’s about targeted efforts to get one’s work in front of receptive audiences, such as Instagram, where it can be seen and discovered. He works with photographers to design a social media plan for effective communication, from personalizing posts to creating interesting tags.

“Artists have to recognize that they’re entrepreneurs,” he said. “They have to show themselves. They have to show the dimensionality of their practice and talk about other artists and their causes.”

During the workshop, Foley also will advise photographers on applying for competitions, approaching galleries, creating a professional portfolio and preparing an artist statement.

Michael Pannier, the SE Center’s founder and director, is offering Foley’s workshop because the art market has changed. The burden of showing and selling art has shifted to the artist. At the same time, many photographers associated with the center want to expand their presence.

“Michael seemed to present fresh ideas on promoting work,” Pannier said, adding that Foley “is not your typical New York gallery owner.”

The idea of “choosing yourself” appears to resonate with photographers. Pannier said the May workshop sold out quickly, but he has started a waitlist for a second one later this year.

Foley’s insights stem from about 40 years of working in art galleries, including his own since 2004. He has learned that people who buy art like to know the story behind it and what the artist went through to create it.

“People are attracted to other peoples’ lives,” he said. “It’s the steps in between. We want to see you with prints on the floor, making an edit.”

Foley follows his own advice. He talks freely about his own blunders and discoveries throughout his own life, often turning them into guidance in “The Photographer’s Report,” a weekly newsletter he started for fine art photographers.

One story recreates the time he was an underage teenager out with four friends at a nightclub. The waitress took their orders first and called in four Tom Collins to a bartender. Thinking that was the name of the drink, Foley also ordered “Four Tom Collins.” And that’s what he got, all stacked in front of him. Foley transformed the embarrassing tale into a lesson about the pitfalls of trying to fit in.

“When we listen to another’s voice and not our own, we end up making work for someone else,” he wrote. “Or drinking four Tom Collins.”

Foley’s own path includes practical decisions based on his strengths — and then abrupt turns fueled by curiosity, intuition and passion.

A psychology degree, acting, darkroom work, making art, pouring coffee, hanging celebrity exhibits and cleaning up vomit are markers along the way to opening his own gallery.

Born in 1964 in Delaware, Foley grew up in Croton-on-Hudson in New York. His first brush with photography was in high school. Using a 35mm point and shoot on aperture priority, he took photos of his friends and turned the film into the yearbook staff. When the yearbook came out, he was amazed to see so many of his images.

“Being published and getting attention for them got me hooked,” said Foley, who, as an unconventional Homecoming King that year, probably knew how to put his classmates as ease with offbeat humor. Consider the homecoming parade, where he wore a paper crown, bathrobe, sunglasses and plastic lei.

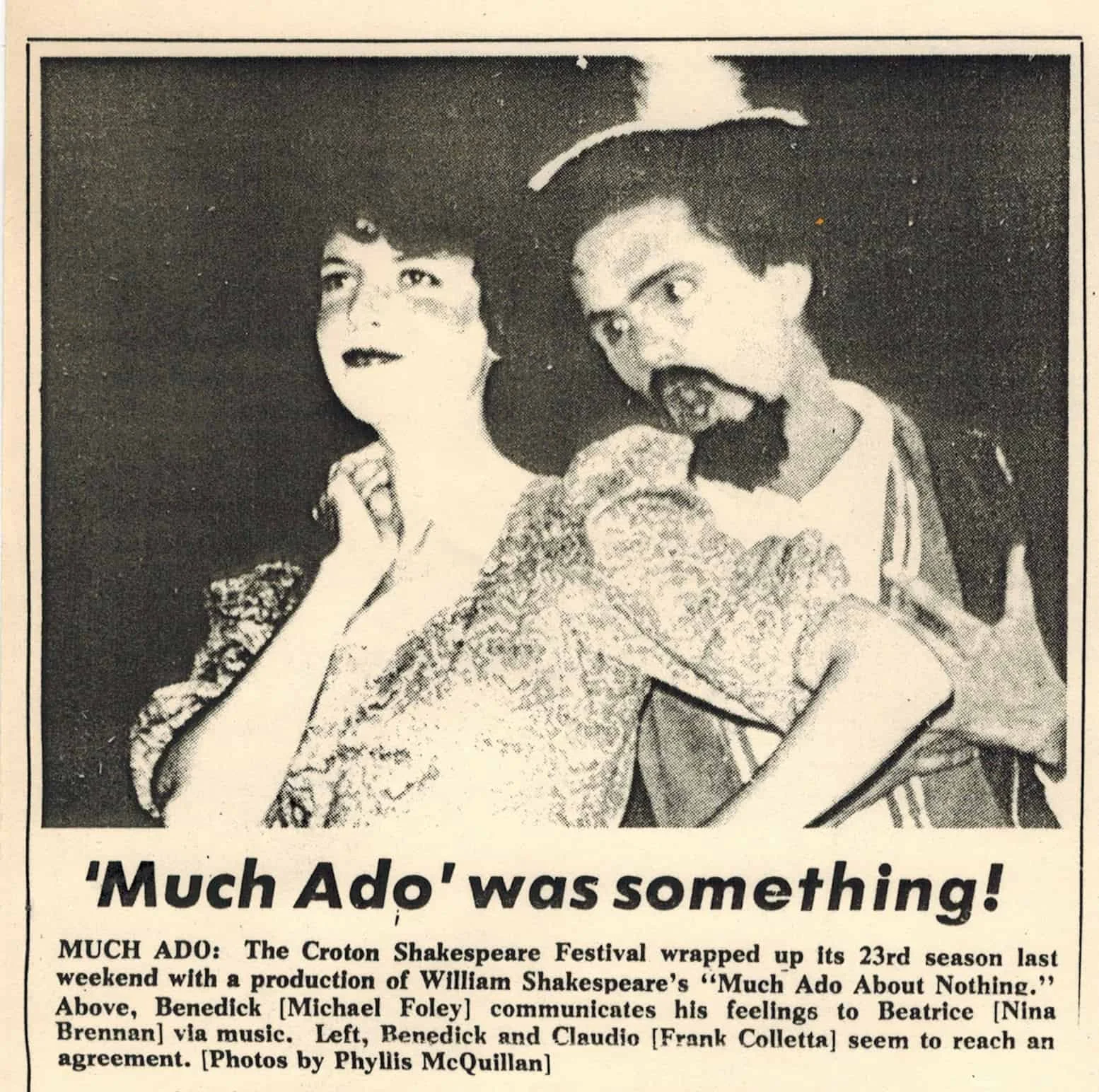

After graduation, Foley majored in psychology at Boston College. With his lively personality, he became a DJ at the college radio station and started acting. He played Benedick, a witty character always making jokes and puns, in Shakespeare’s “Much Ado About Nothing.” During his junior year, he went to London, initially to study acting. But when he registered, he didn’t choose acting classes. He checked the “something else” category and signed up for a darkroom course. It changed his life.

“The darkroom experience was magical,” he said.

Back in Boston, he took another photography class as well as courses in radio, television and communications. Combining his abilities in psychology and theater, he moved to the West Coast to get a graduate degree in drama therapy at San Francisco State University.

Maybe it was the vibe of the city’s artistic scene with its invitation for personal exploration, but Foley, 22, decided to defer the start of graduate school.

“That’s when I decided to pursue art,” he said.

His art included photography, but not as an end in itself. Using a camera gave him an excuse to speak with people and he enjoyed the social connection. But he felt photography lacked a kind of humanity.

Instead, Foley cut up his photos, which always were portraits, to use in collages. He also worked with cut paper and made paintings, and eventually sold and exhibited some of his art.

At that time, in the late 1980s, he could live and make art by working a few jobs. So he cleaned houses, had shifts as a security guard and was a house parent at a youth home. He also worked at a photo supply place and a coffee house before he landed serendipitously at an art gallery.

By chance, the coffee house was near the Fraenkel Gallery, a premier exhibit space for photography in Union Square. Foley had stumbled upon the gallery and got to know the staff. One day when he was at the coffee house, a staff member showed up with a question. Had he ever thought about working in a gallery?

“They had a sense that I understood the gestalt of a gallery,” he said, adding: “I got the job mostly because they like me.”

His starting salary was $18,000 a year, which sounded like a million bucks to him: “I was on top of the world!”

For the next five years, he worked as a preparator, a person who assists with displaying, storing, cleaning, cataloging, shipping and installing art exhibits. But more than the position and money, the gallery trained him to see, analyze, discuss and experience photography.

“That’s where I learned everything I know,” he said.

The gallery was owned by Jeffrey Fraenkel, a pioneer in fine art photography affectionately known as “The King” by his staff. Fraenkel carried several influential and controversial photographers, including: William Eggleston, who helped propel color into the realm of fine art with his vivid images of mundane scenes; Robert Mapplethorpe, who focused on celebrity portraits, nudes and homoerotic themes, sparking debate over obscenity; and Garry Winogrand, a street photographer who portrayed social issues.

Fraenkel tutored Foley on the importance of sequencing in hanging images and the relationship of images to each other. Foley relied on those lessons when he nervously hung a photography exhibition by the actor Richard Gere, who quietly watched Foley place his photos on the walls.

“I didn’t know he was behind me,” Foley said. “And then I heard a voice say, ‘I like what you do.’”

What impressed Foley about the experience was seeing Gere, a celebrity but also a practicing Buddhist, come into the gallery with “a beginner’s mind,” and appreciate his abilities.

By 1997, Foley had lived in San Francisco for 11 years and was restless for a change.

“I felt like the tide was going out and I didn’t see a future there,” he said. “And I missed the East Coast, the energy of New York and the seasons.”

Foley returned to New York City to work as a preparator for the Howard Greenberg Gallery, which carried historical photography, primarily from the 50s, 60s and 70s. He described the staff as twice as big, with bigger personalities and more politics.

“Landing in New York City was a big step, but it was a soft landing,” he said.

Eighteen months later, Foley accepted a job at the Edward Carter Gallery, but this time to run the operation and curate exhibitions. The owner, Edward Carter, was a photographer with considerable wealth.

“I was in over my head,” Foley said. “I had to do everything. I had to make sales and I had never sold art before. I had real responsibility.”

As Foley juggled these challenges, he also saw the differences in how he and Carter viewed art. At times, it created friction, especially when he wanted to show work from artists he liked.

“He would remind me that Ansel Adams was the gold standard,” Foley said. “I wanted different things.”

One day Foley saw a fax from a gallery looking for a preparator to assist with a move. Yancey Richardson, the gallery owner, hired him as the point person, but he stayed on as the gallery’s de facto director. After four years, he was ready for another change.

“I had run to the end of the diving board,” he said. But where to jump was the question.

And then it hit him: “What if I went back to being an artist?”

Just like years earlier in San Francisco, he needed a job for the money so he had time and energy to make art. Friends helped him find work at a nightclub, but it came with unanticipated demands, like lifting heavy things.

“Physically, it was too much,” he said. “I was moving trash cans and cleaning up vomit.”

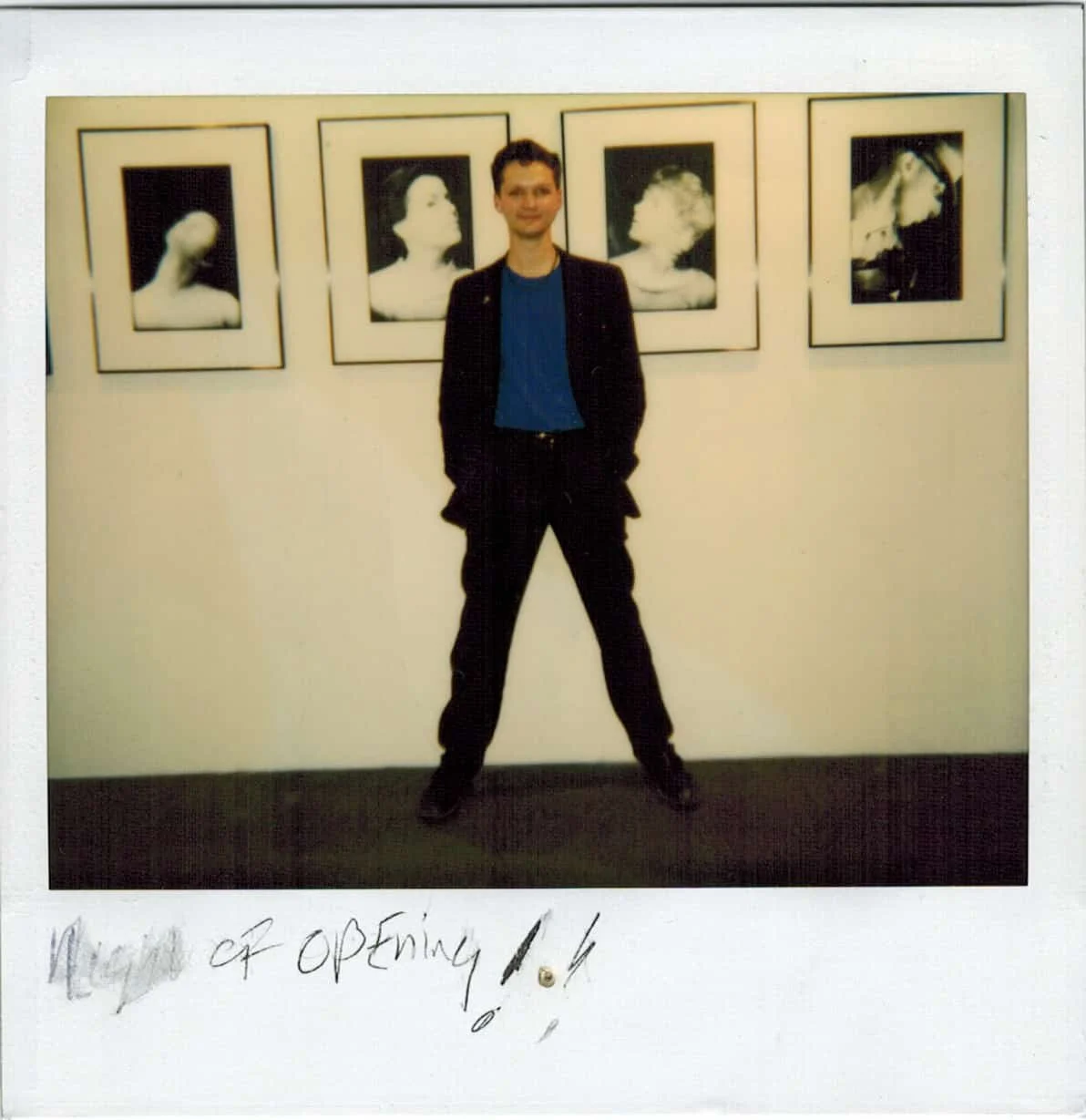

About six months later, Foley decided to open his own gallery. He got a Small Business Association loan and sold some photos he had purchased for his own collection.

“I realized I had to take the initiative and design my own life or work for other galleries,” he said.

While he knew how to run a gallery, he didn’t know the business end of it. He learned on the job. Art suddenly became a tangible good with a price tag. He had to figure out whose work would sell — and what work he was willing to show.

“My number one priority was: Do I like it? Is it brash? Is it novel?”

He found he wasn’t successful selling work that someone else had labeled as “hot, trendy and the right ethnic group.”

Foley said the gallery’s best years were 2006-2007 before the Great Recession; after that, the art scene never came back the same way.

The economic crisis forced Foley to innovate. In 2010 he co-founded the Exhibition Lab for students to study fine art photography and develop a body of work. The Lab, which is limited to nine students over six months, concludes with individual exhibitions lasting three weeks.

“It’s long-term direction and it ends with a celebration,” he said.

The recent pandemic sparked more innovation. For people visiting his gallery, they might notice new shelves. Foley plans to open a book store in the back, focussing on photography books by lesser-known photographers. He envisions book talks and signings.

“It will be for people who won’t have a name to carry them out there. “It gives an opportunity for placement and for a platform.”

He also sees the bookstore as a new way for people to engage with the gallery. His goal is to bring photographers together — but also to encourage them to be distinct — to develop their personal vision. It doesn’t mean shooting only one subject, but bringing their sensibility to whatever they photograph.

Ironically, he has observed that many photographers don’t want to be different. They want to do things ‘the right way” and measure themselves based on established principles. Foley instead steers photographers to take the photos only they can take. Photos that have their “fingerprint.”

“The hardest thing is do,” Foley said, “is have enough confidence to do something different.”

Linda Hosek is a photographer, journalist, and avid supporter of the SE Center for Photography and a participant in many of its activities.

The SE Center’s workshop series covers all aspects of photography and challenge, encourage and inspire the photographer in all of us. During the workshops, our complete focus is on you, the photographer.

For more about the series and other events at our fine art photography gallery please visit our Workshops page.