To understand Dan Sackheim and his photos, you have to embrace the mysteries of the night — its quiet terror and haunting beauty — and imagine the things you can’t see.

“It’s what’s in the shadows that I’m drawn to,” said Sackheim, a Los Angeles television and film producer who has applied his visual and storytelling skills to photography to create cinematic images inspired by the film noir genre.

“I was influenced by the style of noir, the sense of anxiety and alienation that existed,” he said. “I wanted to channel it into my work."

For the past few years, he has been building on that theme, creating a collection he calls “Unseen,” which is on display until September 27 at the SE Center for Photography in Greenville, South Carolina. The reception is 6-8 p.m. Friday, September 6.

Many “Unseen” images feature dramatic LA scenes, but the collection isn’t about a destination. It’s an emotional exploration of what lies beneath the surface, projecting a fatalistic mood with menacing overtones. Photos read like scripts of imagined figures living between shafts of light and walls of darkness in an urban jungle.

Sackheim’s work represents the top choice of three jurors, including Michael Pannier, the center’s founder and director, who wanted to create an exhibition of portfolios: “We were looking for cohesive bodies of work, both in storytelling and presentation.”

For this first portfolio call, the jurors reviewed 190 entries, narrowed the field to 30 and eventually selected 10, which the center exhibited last August. They then selected Sackheim’s work for a solo show to open in 2024.

“Being a fan of the film noir genre, it spoke to me immediately,” Pannier said. “It’s the cinematic qualities and the subtle inclusion of elements, such as the lone figure, that really makes each image.”

With “Unseen,” Sackheim said he wanted to give viewers a feeling of a life that. was lived, of spirits that linger.“I was trying to create the sense of something that was once there, but now gone,” he said. “I was trying to evoke nostalgia.”

And a sense of vulnerability, as in “LA Noir.” The image shows a lighted movie theater sign in which each letter of “Los Angeles” is stacked vertically. A tiny figure silhouetted by a streetlight walks below, flanked by darkness.

LA Noir © Daniel Sackheim

“When you want to diminish someone and increase their vulnerability, you shoot them from looking down,” he said, adding that he used a drone to create that image. Sackheim also likes to shoot with a point of view. “A Salaryman’s Night Out” shows a man in a dark suit, hunched over in a counter in a steamy Tokyo noodle bar. The viewer sees only his back and broad shoulders — but knows the story is about him.

“I want the viewer to know what he looks like, but not show what he looks like,” Sackheim said.

It is ironic that Sackheim creates a shadowy, enigmatic world with his noir imagery, but had a paralyzing fear of the dark as a child.

“So terrified was I of the imagined creatures hiding under the bed, or lurking within the dark recesses of my closet, that I would often drift off to sleep with a flashlight clutched in my hand,” he said.

Sackheim grew up in LA, the birthplace of film noir, but spent considerable time in New York after he was 16. His father, William Sackheim, lived in the city and was an Emmy-winning writer and producer who loved the arts. They would spend Sundays in museums and became drinking buddies after Sackheim turned 18.

In Sackheim’s early 20s, he developed an interest in photography — in fact a love for it — but didn’t pursue it as a career. Instead, he went to engineering school, responding to a long-time fascination with how things work. But the classes he took didn’t hold his interest and he dropped out.

“I didn’t know what I wanted to do,” he said. “I was directionless.” On a lark, he decided to audit drama classes at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) and something clicked. That was a promising start, but not enough to satisfy his father, who wanted him to get a job if he wasn’t a full-time student.

Sackheim found work at a commercial post-production house where he maintained editing equipment and machines. “I was introduced to the basics,” he said. “Within six months, I was working as an editor.”

He wanted to go deeper into editing and asked his father if he knew anyone who could help him. His father introduced him to Margaret Booth, who Sackheim described as “a scion of MGM,” the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer motion-picture studio. She had received an Academy Award nomination in 1935 for “Mutiny on the Bounty.” She also worked on other celebrated films, including “Camille" with Greta Garbo in 1936, “The Way We Were” in 1973 and “The Goodbye Girl” in 1977.

It’s worth noting how respected Booth was. The Guardian newspaper described her as a pioneer of “invisible cutting,” the classic editing style in which the transition from one clip to another is as seamless as possible. The audience essentially experiences the flow of shots within a sequence while being absorbed in the narrative.

Booth was 86 when she took Sackheim under her wing: “She was putting together a retrospective of John Huston (an American film director, screenwriter and actor). I would sit with her and take down notes as we watched it. I thought if they are paying me to do this, this has to be the best job on the planet.”

Sackheim continued to learn film editing primarily under Booth's tutelage, saying that "working for Margaret was my film school." He also picked up techniques by watching movies and reading about directors -- and did work for years as an assistant film editor. But he eventually wanted to advance.

“I was in my 20s — they weren’t going to give a film editing job to me,” he said. So he moved to TV, started editing there and soon became a producer.

That’s where he met Dick Wolf, the legendary producer known for the “Law and Order” franchise. Sackheim said he worked on the series pilot in the mid-80s. Although it initially didn’t sell, the show finally landed with NBC with the first episode airing in 1990.

The Jaws of Light © Daniel Sackheim

Around that time, the ever-restless Sackheim got a tempting offer for a bigger producer job. But he said Wolf asked if he wanted to direct an episode of “Law and Order” as a way to keep him on.

About three years later, he won an Emmy for directing an episode of “NYPD Blue.” That 1994 award set him on a career path during which he worked on television series such as “True Detective,” “Game of Thrones,” “Jack Ryan” and “The Americans.”

You might think he would have been thrilled by his success. But behind the scenes, perhaps in the shadows, he didn’t feel great about things. Work was hard and he was stressed out all the time. He said he also suffered from imposture syndrome, a phenomenon in which people feel like they aren’t good enough or don’t deserve their accomplishments.

“I loved being a director, but not directing,” he said.

Being a perfectionist was part of the problem. He would spend time on details and nuance, finding it hard to walk away without making the episode the best he could. But he also felt pressure to shoot faster and he said he pushed the limit as far as he could without damaging his reputation.

“Every hour you go over is immensely expensive and immensely unappreciated,” he said.

But he persisted. His directorial credits include “Servant,” “Better Call Saul,” “Jack Ryan,” “The Leftovers,” “Man in the High Castle,” “The Walking Dead” and “Lovecraft Country.”

Sackheim also directed feature films, including “The Glass House,” which stars Diane Lane, Stella Skarsgard and Leelee Sobieski.

A couple of things about a decade apart rekindled his early interest in photography. The first was the 100-day strike by the Writers Guild of America that began in late 2007. In search of a creative outlet, he enrolled in photography classes at Art Center College of Design in Pasadena.

“I picked up my camera and went back to school,” he said. The second was the pandemic, which caused most productions to shut down. Again, he reached for a camera (he uses a Leica M11 with a 24mm lens or a Leica SL2-S), and photographed for hours, often returning to certain locations. He wanted to tell a story based on a place.

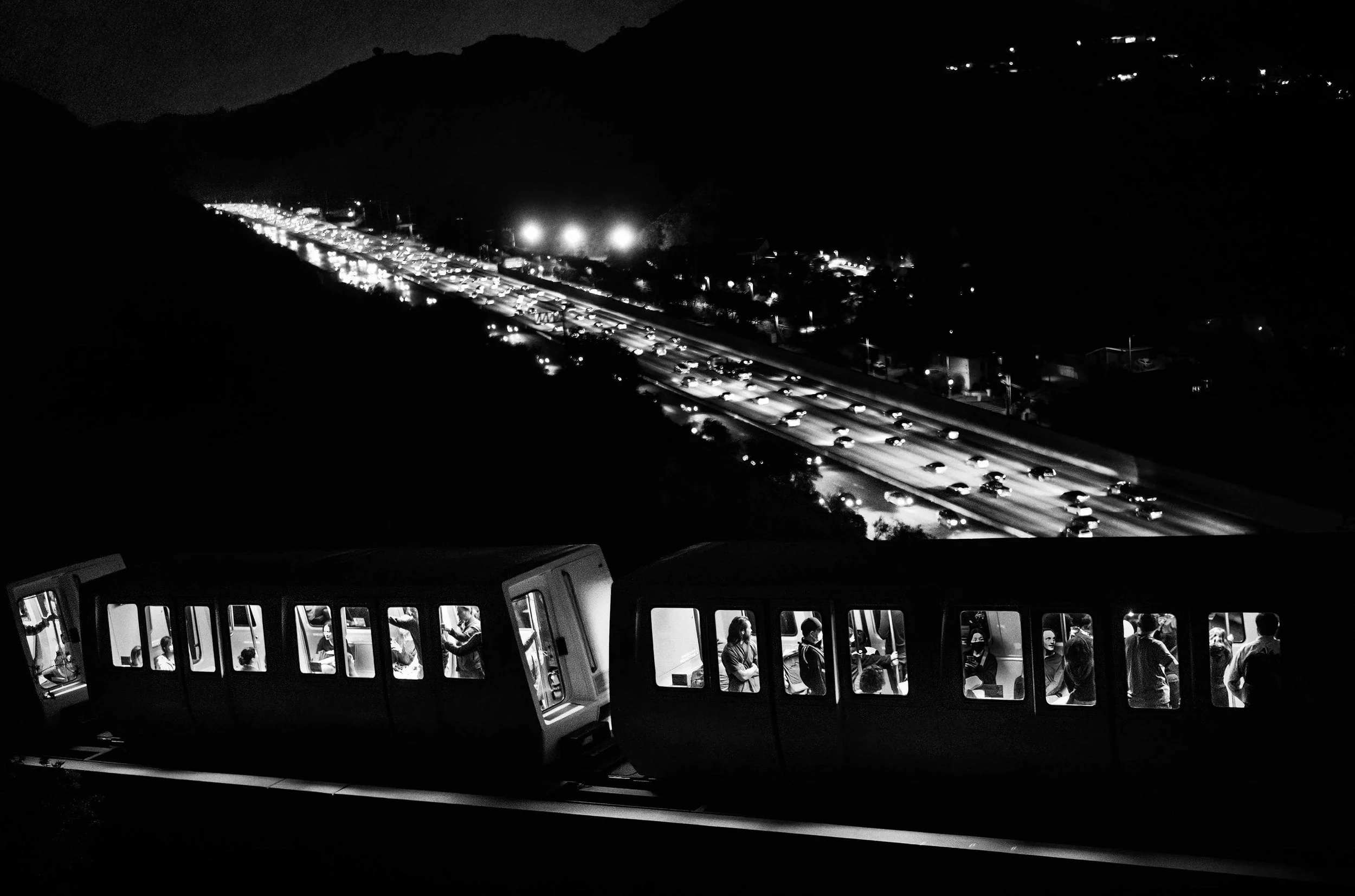

Homeward Bound © Daniel Sackheim

An example is “Homeward Bound,” a night scene that shows people sitting in a lighted tram as they travel from the Getty Center atop a hill down to a parking lot. The tram, in the foreground, visually intersects with a section of the busy, light-streaked 405 freeway in the background.

Sackheim said he got the idea for the photo while sitting in freeway traffic and noticed the tram rolling by. It took him four visits and thousands of shots to get the moment or “ecosystem” he wanted: enough riders, the right sharpness and the right light.

“It’s a fast-moving tram and you have to freeze it to show the people inside,” said Sackheim, who used a tripod, shot at f2 and focused manually.

He also had to wait until it was dark — but before the center closed — giving him about an hour to work.

“I got that image on the third try and went back for one more to see if I could get something even better,” he said. “I didn’t.”

Sackheim’s approach to this image represents how he works. The tram is like a fishing hole. Sackheim would cast into it to fish for images — but throw most of them back.

“There are people who fish and people who hunt,” he said. “I do very little hunting. I’m drawn to light and wait for something to happen. I can sit for hours in a spot.”

© Linda Hosek

Even though Sackheim spent much of his career sequencing moving images, he finds a fixed image just as compelling. It highlights a specific slice of time — one he can choose.

“It begs the question of what happened just before and just after,” he said. “It poses as many questions as it answers.”He also has applied some his directorial insights to his photography, explaining that a scene needs to be about two things: “It should reveal something new about the character and suggest a hidden agenda, pent-up feelings.”

Sackheim believes that “no one succeeds without being given a leg up” and credits several photographers and artists for inspiring him.

Just a few include Edward Hopper, the American painter known for his themes of isolation and alienation; Pablo Picasso for his ability to constantly change his style; Sebastiao Salgado, the Brazilian documentary photographer, for his use of light; Henri Cartier-Bresson, the French photographer known for capturing “the decisive moment”; Alex Webb for his complex layered photos in which “every layer has a story”; Australian Trent Parke: “He’s my favorite black-and-white photographer”; and Garry Winogrand, an American street photographer who captured social change in the individuals, crowds and energy of public life.

“I love Garry Winogrand, but I would never be able to do that style,” he said, adding that he’s basically too shy to put a camera in someone’s face.

Sackheim also gives credit for his creative growth to Susan Burnstine, an LA- based fine art photographer known for ethereal images. Like Margaret Booth, Burnstine took him under her wing and then encouraged him to enter competitions.

And that has been rewarding. In addition to the current exhibit in Greenville, Sackheim has enjoyed solo or group shows during the last two years at galleries in LA, NY, London and Naples. He also is represented by the Susan Spiritus Gallery in Southern California.

“The response has been really great, really heartening,” he said. “Of course, it builds ambition.”

He likes seeing his images on gallery walls and hearing people comment, a big difference from the producing and directing he does in his day job. “The thing about television,” he said, “you rarely get to see people reacting in real time to your work.”

At this point, he likens photography to “a second act.” And the more he pursues it, the more he wants to evolve, in part to avoid getting bored with his own work. One direction is to do more elaborate storytelling and build sequences. Another is to push beyond the formality of his current imagery.

“I want to infuse my work with more dynamism and have rougher edges,” he said.

Whatever he does, he likely will apply his own sense of perfectionism to his photos and scrutinize them without mercy. So even though he may shoot thousands of images of a subject, what he shares will likely be a fraction of that.

“If I get 10 good shots a year,” he said, “that is an accomplishment.”

Sackheim’s website: danielsackheim.com

Susan Spiritus Gallery website: susanspiritusgallery.com